By Terry Flanders CPP; CPOSHP

There is a social war on the horizon, and we need to prepare now. Our enemy is well known, purposeful and deceitful. Tactics involve the use of chemical weapons. Civilian casualties and costs were high last time we engaged, and we were unable to protect ourselves or our families.

As the Russians weaponised social media in the 2016 US Presidential elections, recent research provides evidence that the Taliban may very well be weaponizing opium to target the west indirectly and America directly. The data collected by national and overseas agencies was for the general purpose of monitoring plant-based and chemical based illicit drugs. Findings, when viewed collectively, present a disturbing trend that if correct, supports the view that heroin should no longer be considered an illicit drug but a weapon of social destruction.

If an old enemy was creeping up towards us, would we notice in time to react? Or, like the frog left in slowly heated water; have we become too complacent or self-indulgent and slow to react?

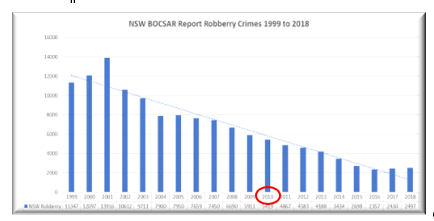

Incremental changes can go unnoticed by individuals and groups exposed to that change. As a society, Australians have been exposed to a positive incremental change since 2002. That change is a decrease in reported property crimes. It’s argued by some that our property crime statistics are reflecting levels of reported crime from the 1980’s. Property crimes include robbery offences and reported robbery statistics[i] (Graph 1) for NSW provide an excellent example.

Graph 1 NSW BOCSAR Data

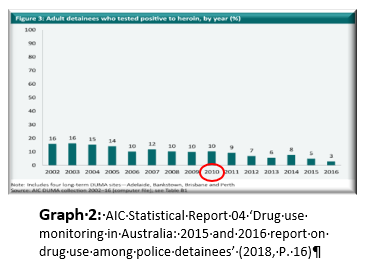

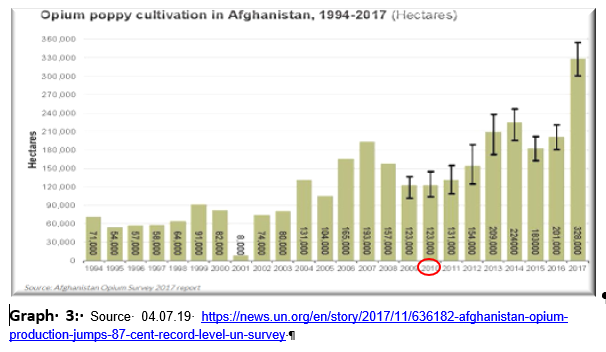

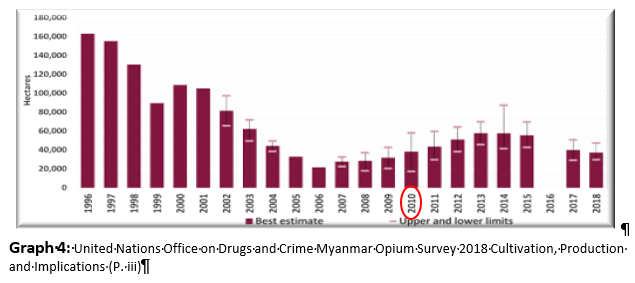

Note: The year 2010 has been highlighted in all Graphs.

The data in Graph 1 shows that the percentage of reported robbery offences between 2002 (n. 10,612) and 2016 (n. 2,357) fell by 78 per cent.

The ‘Drug Use Monitoring in Australia’ (DUMA) program is a research project conducted by the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC). The program began in 1999 to monitor the illicit drug use of police detainees. Volunteers submitted urine samples within 48 hours of arrest and were surveyed. The samples and survey results were analysed to inform or guide researchers on the illicit drug problem in Australia. Four sites were selected initially to conduct the research, this has grown to five sites in Sydney (x2), Adelaide, Brisbane and Perth.

The data in Graph 2 shows that 16 percent of DUMA participants in 2002 were found to have heroin in their system. In 2016 surveyed DUMA participants with heroin in their system fell to 3 per cent. This is a decrease of 81 per cent, similar to the decrease in robbery crimes over the same period. A correlation that supports the argument that there is a causal connection between lower heroin use and lower reported robbery crimes. Correlation doesn’t always mean causation. The more correlations, the stronger the argument that lower crime rates are associated with lower heroin use. So, let’s consider the following.

Findings from the most recent DUMA research[ii] related to crime and illicit drug use include:

- Eighty-two percent (n. 319) of detainees whose most serious offence was a property offence tested positive to at least one drug, with amphetamines being the most common (63%; n. 243) followed by cannabis (45%; n. 175).

- Seventy-one percent (n. 394) of detainees whose most serious offence was a violent offence tested positive to at least one drug, with amphetamines being the most common (44%; n. 243) followed by cannabis (42%; n. 232).

- Detainees whose most serious offence related to drugs were most likely to test positive to amphetamines (59%; n. 112) followed by cannabis (41%; n. 78), benzodiazepines (16%; n. 30), opiates (16%; n. 31) and cocaine (3%; n. 6).

- Thirty-two percent (n. 1,407) reported that illicit drugs (cannabis, heroin, methamphetamine, ecstasy) contributed to their detention.

DUMA research indicates that the use of methamphetamine drugs has increased, as the use of heroin has decreased. Illicit drug use is an acquisition crime[iii] [iv]. This means that illicit drug users commit crimes in order to acquire resources (cash or property) to purchase their illicit drugs. From my experience, street heroin costs more to purchase than other illicit drugs. Therefore, heroin users are likely to commit more crimes then other illicit drug users. As heroin addiction in a population grows and heroin use increases, more crimes can be expected.

As an acquisition crime, illicit drug use impacts our society across all levels and has a tangible and intangible cost. Criminologists have been calculating the cost of crime in Australia for some time now. Over that period, calculations have changed or expanded so comparing costs of crime figures over time is problematic. Table 1 below provides an example of the variance in crime costs from different sources.

Table 1: Examples of variances in crime and illicit drug use costs

| Reference Source | Year | Annual Crime Costs | Annual Illicit Drug Crime Costs | Annual Illicit Drug Social Costs |

| AIC Trends & Issues No 39 ‘Estimates of the Cost of Crime in Australia’ | 1992 | $16.8B – $27B | ||

| National Drug Strategy ‘Counting the Cost: Estimates of the social drug abuse in Australia 1998 – 9’ Monograph Series No. 49 | 2002 | $5.1B | $6.1B | |

| Organised Crime and Public Sector Corruption, AIC Trends & Issues No 444 | 2013 | $10B – $15B | ||

| Australian Crime Commission Annual Report 2012 – 13 | 2013 FY* | $8B | ||

| Australian Crime Commission: The Costs of Serious & Organised Crime in Australia | 2014 FY* | $36B | $4.4B | |

| Australian Crime Intelligence Commission: Organised Crime in Australia | 2017 | $36B |

*Denotes Financial Year as opposed to calendar year.

Illicit drug use is not only a crime on its own, it has a societal cost that we all bear disproportionally. In fact, to quote findings of one research[v] project (bold added):

“Of particular interest is the fact that the government sector bore a relatively small proportion of the tangible costs of drug abuse (24 per cent of alcohol-attributable costs, 11 per cent for tobacco and 33 per cent for illicit drugs). In all cases business bore a greater proportion of the burden (39 per cent for alcohol, 30 per cent for tobacco and 57 per cent for illicit drugs). By their nature, all intangible costs are borne by individuals.”

Illicit drug use in any population is a complex issue with many variables that can impact the illicit drug market. Some of those variables include economic, political, regional, environmental, supply chains, social or cultural and consumer demand. All factors that may on their own or collectively converge to change consumer habits leading to a reduction in illicit drug use and crime. Another consideration is the competitive rivalry between plant based illicit drug producers and chemical based illicit drug manufacturers as they compete for market dominance. Before exploring some aspects associated with plant and chemically based illicit drug production and supply, it would be appropriate to provide a brief background of the two major illicit drug rivals, heroin (plant) and methylamphetamine (chemical)

Heroin is manufactured from opium harvested from poppies. In the 19th Century what we would now call the largest commercial supplier of opium was the East India Company. When the sun never set on the British Empire, East India Company ships laden with silk and other products from China were empty on their return trip. The East India Company began growing opium in India and once empty clippers now returned to China laden with opium for on-sale to the Chinese. After two ‘Opium’ wars to halt the trade in opium, which the Chinese lost. The Chinese increased opium production at home to break the devasting effects that opium addiction had on their population. In other words, the Chinese used economic forces to break the trade in opium.

About the same time, Chinese migrants left their homeland for goldfields in America and Australia bringing opium to the world. Global opium addiction increased, and well-meaning scientists developed a cure for opium addiction in the early 1920’s. They called this wonder drug morphine. It was 100 times more addictive than opium and worked well as it stopped opium addiction. A few years later more well-intentioned scientists developed a new drug to stop morphine addiction. It was called heroin. It also worked well as it was 1000 times more addictive than opium.

The medical benefits of morphine were appreciated and now there are licensed poppy farms in the west that harvest opium for the legitimate manufacture of morphine. Due to their addictive nature opiates were classified as an illicit drug. Later in the 20th Century an illicit drug market grew. Now Afghanistan is the world’s leader producing 90 per cent of the world’s opium. Afghani opium production is controlled by the Taliban and supply targets the west. In Australia, because of supply chain issues, our heroin is mainly produced in the Golden Triangle or Myanmar.

Coalition forces invaded Afghanistan in 2001 and opium production was interrupted but not stopped. In fact, in 2017 Afghani opium yields[vi] increased by 87 per cent from 2016 to 9,000 metric tonnes. Over the same period the land to cultivate poppies increased by 63 per cent to 328,000 hectares. The increase in opium production could be linked to the withdrawal of American troops from Afghanistan. It could also be argued that the Taliban have weaponised opium in their continuing war against the west. If true, one would think that America would be targeted first.

Graph 3: Source 04.07.19 https://news.un.org/en/story/2017/11/636182-afghanistan-opium-production-jumps-87-cent-record-level-un-survey

Myanmar’s heroin production has also been impacted regionally by conflicts between warlords vying for control of the heroin trade. As opium harvests in Myanmar fell, Taliban opium production picked up. Given the current rate of opium being harvested eventually this must lead to a global oversupply of heroin.

Myanmar Opium Production per hectare

Graph 4: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Myanmar Opium Survey 2018 Cultivation, Production and Implications (P. iii)

Although there is an increase in opium production in Myanmar from 2010 until 2014, production levels were much lower than before and what was produced may have been supplied to locals as opposed to Australian consumers.

Another factor that has come into play is methamphetamine as a competitor for heroin, not only in Australia, but also within the Golden Triangle region. This has also affected opium production in Myanmar and drug cartels are now moving away from opium harvests to illicit chemical-based manufacturing.

Methamphetamine once would have fallen under the category of a ‘designer drug’ as the formula was constantly changed (redesigned) to negate criminal laws regarding possession of the drug. Methamphetamine was produced[vii] by Germany during the 2nd World War to enhance the combat abilities of their troops.

The drug saw resurgence during the Korean war and after that war ended, Japan during its economic recovery promoted the use of methamphetamines to workers rebuilding the country. This had a disastrous effect and violent crimes rose dramatically as users had psychotic episodes from lack of sleep caused by drug over-use.

Methamphetamine and other chemically based drugs are still used globally by defence force personnel to enhance combat capabilities.

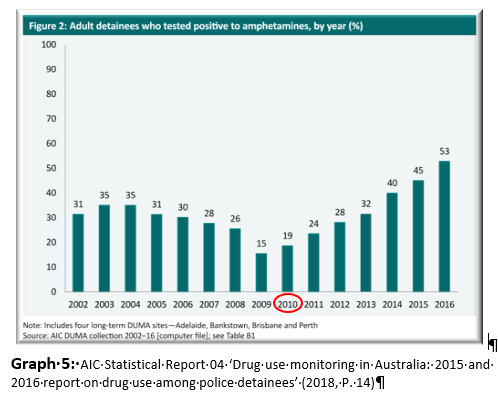

Data from the 2018 DUMA report relating to methamphetamine use in Australian police detainees is shown below in Graph 5.

Graph 5: AIC Statistical Report 04 ‘Drug use monitoring in Australia: 2015 and 2016 report on drug use among police detainees’ (2018, P. 14)

In Australia, with the reduction in heroin supply illicit drug users also appear to have moved to using methamphetamine. Methamphetamine unlike heroin is a stimulant. This may be one reason younger illicit drug users are moving away from traditional illicit drugs, as heroin use at rave parties would be inconsistent with attending a ‘rave’ party. Or perhaps heroin is seen as an ‘grandpa’ drug and millennials are seeking to find a newer experience.

Clearly the data collected from DUMA research, shows the use of methamphetamines in Australia is increasing. Is this a new trend reflecting modern day illicit drug users change in preferences? Or is better marketing by chemical based illicit drug producers the cause? It’s my experience that there is usually a multitude of factors behind problems. As Donald Rumsfeld famously stated there are known knowns and known unknowns as well as unknown unknowns.

The evidence supports the argument that a fall in heroin use has led to a fall in reported property crime in Australia. Is there evidence to support the argument that the Taliban are weaponizing heroin to target America?

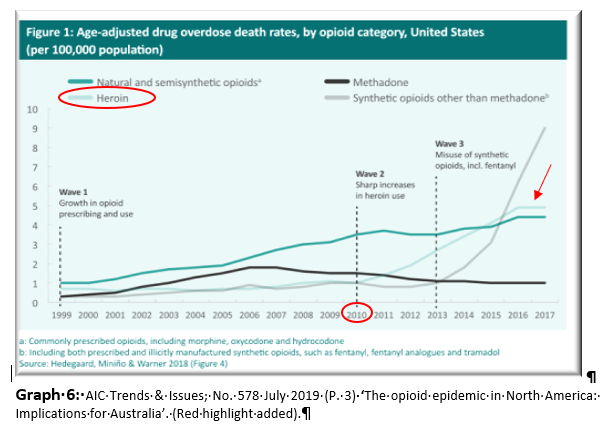

Graph 6: AIC Trends & Issues; No. 578 July 2019 (P. 3) ‘The opioid epidemic in North America: Implications for Australia’

The data in Graph 6 (highlights added) shows there has been a steep rise in the use of heroin in America since 2010. This is contrary to the Australian experience. The 2010 rise in heroin use in America coincides with the rise in opium production in Afghanistan (Graph 3), the fall in opium production in Myanmar (Graph 4) and the rise of amphetamine use in Australian police detainees (Graph 5). Co-incidence or a warning that there is an illicit drug storm coming?

At this time, the Australian marketplace is not being flooded with cheap heroin and so it seems, neither is Europe. Research from ‘European Drug Report 2018: Trends and Developments’ (P. 52) states:

“According to available trend data, the number of first-time heroin clients more than halved from a peak in 2007, to a low point in 2013 before stabilising in recent years”.

An emergent property that may impact conventional illicit plant-based drug supplies is the recent pharmaceutical production of licit chemical opioids like fentanyl. A practice that has become clear in the American experience is mixing fentanyl with heroin. This may be a tactic by heroin suppliers to increase market share by diverting chemical opioid users over to heroin.

The Taliban are not friends of America. Arguably the Taliban used funds from opium harvests to pay for their war against America. Now that war is coming to an end, why go to the trouble and cost of increasing opium production? I can only speculate on the answer and it would seem that given the rise in heroin use in America since 2010, Afghani opium is being used to target the needs of American heroin addicts. If true and left unchecked, then heroin is being used in America as a weapon for social destruction. How long will it take for the overflow to impact other western countries?

One very likely outcome in any war between drug suppliers for market share will be an increase in property and violent crimes in Australia. There seems to be a singular difference between the Taliban and Myanmar drug cartels. The difference is purpose. The Talabani purpose is ideological and involves continuing the war against the west. The purpose of the drug lords in Myanmar is most likely economical driven by the need for asset acquisition[viii]. Converting illicit drugs into cash as illicit drug users convert cash into illicit drugs.

One characteristic not considered in any of the crime costing formulas is the social cost of enforcing laws. Mental health issues are on the rise in NSW Police[ix] In March 2019 Pat Gooley from the Police Association of NSW described[x] the issue as a mental health emergency that has cost the government $800M over the last five years. Funds that are being diverted away from law enforcement. Findings from a 2019 Senate Inquiry[xi] showed that the ‘mental health emergency’ is not confined to NSW first responders. If emergency service providers cannot cope now when crime rates are at their lowest in 17 years. How will they cope if crime rates increase to 2002 levels?

We have become complacent in our modern-day low crime society. For example, concierge models have replaced pop-up counter screens in banks and credit unions. Should we wait until crime rates increase to pre 21st Century levels before acting or should we plan and prepare now for the very likely future that will see an increase in illicit drug use and crime. An increase that, like the Chinese experienced, is very likely to impact us all personally.

In order to be successful as security professionals we need to plan for failure. Counterintuitively failure is a pathway to learning, leading to success. Planning for emergencies [xii] should happen well before the emergency strikes. We need to start planning and preparing now for what is a real threat to our society.

At the micro level as security industry professionals we need to start planning to build adaptive security systems to increase resilience in preparation for rising crime rates. At the macro level, the Government needs to start preparing for the challenges that illicit drug oversupply may have on our services including the judicial system and social infrastructure.

Having fought in the last war on illicit drugs, the strategies and tactics that were in place then didn’t work. A top down bottom up approach is needed. One that targets importers, producers, suppliers and manufacturers of illicit drugs from the top while using programs based on social responsibility to curb illicit drug use from the bottom. Alternatively, we could do what the Chinese did 150 years ago, break illicit drug cartels economically by legalising illicit drug use, treating user’s addictions in monitored health settings while working towards rehabilitation. Such a practice would certainly be safer and much cheaper given the historical crime and costs associated with illicit drug use.

What I do know based on the evidence is that heroin, whether it has been weaponised or not, will be flooding the global marketplace and while Australia may be downstream from that flood now. That flood is coming.

[i] Source NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research

[ii] Patterson et al (2018); ‘Drug use monitoring in Australia: 2015 and 2016 report on drug use among police detainees’; AIC Statistical Report 04 (P. xii)

[iii] Intergovernmental Committee on Drugs National Drug Strategic Framework Annual Report 2003–04 to the Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy (May 2005 P. 14)

[iv] Goldsmid & Willis; ‘Methamphetamine use and acquisitive crime: Evidence of a relationship’ (October 2016) AIC Trends & Issues No. 516

[v] National Drug Strategy (2002): ‘Counting the cost: estimates of the social costs of drug abuse in Australia in 1998-9’; Monograph Series No. 49 (P. 63)

[vi] UN News November 2017 ‘Afghanistan opium production jumps 87 per cent to record level – UN survey’.

[vii] Military History Now.com (2018) ‘Combat High a brief but sobering history of drug use in wartime’.

[viii] Note: The lowest level of Maslow’s Hierarchical Order of Needs suggests that people are motivated by evolutionary forces to collect ‘somatic’ assets i.e. food, water shelter for the purpose of reproduction. We no longer hunt and gather in the forest. We hire ourselves out and work for cash. We convert the cash into food, water and shelter for the purpose of reproduction. In modern times our asset lists include tangible assets (somatic resources, cash, property etc); intangible assets (proprietary information, intellectual property etc) and abstract assets (love, respect, recognition, ideology etc). Different individuals and groups apply different values to the three asset classes. In the context of this article, Taliban ideology may be more important than any tangible asset. The theory of ‘asset acquisition’ is a work in progress that adds to criminal motivation as described by rational choice theory.

[ix] NSW House of Representatives (2018) Portfolio Committee No. 4 – Legal Affairs Emergency services agencies

[x] Daily Telegraph Article ‘Calls for funding for support programs with 300 police leaving the force each year’ Dated 19.03.2019.

[xi] The Senate Education and Employment References Committee (2019) The people behind 000: mental health of our first responders

[xii] AS/NZ 3745:2010 Planning for emergencies in facilities (as amended)