The role of Youth Justice officers is to supervise young people in custody, but given the sensitivities of their work, no media recording is allowed in their facilities. So how can future officers be recruited, trained, and upskilled without compromising young people’s privacy or centre security? Careful recruitment and immersive training are particularly important, given the rigours of the job.

Now enter final-year University of Sydney computer science student teams, who co-developed virtual reality simulations for the state’s youth custodial centres, under the guidance of the University’s Digital Innovation team (TechLab) and Youth Justice’s Organisation Development and Training team (YJNSW).

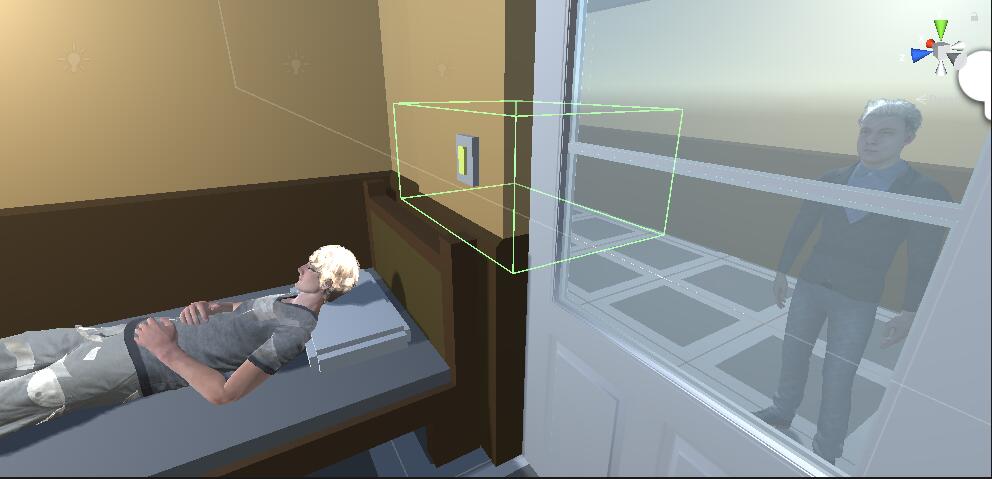

One team tackled the project, ‘A virtual immersive walkthrough of a day in the life of a Youth Officer’. This involved creating around 18 virtual reality scenarios a Youth Officer might experience at a Youth Justice custodial centre.

For example, how officers move detainees from one area of daily activities to another; supervising them on a sports field during recreation time; and supervising them during lunchtime. As backgrounds for their simulations, the students used images of a youth justice centre, previously captured with a 360-degree camera.

“It was important to use actual Youth Justice spaces as there are interesting nuances to these centres,” said project lead and student mentor Ms Viji Venkataramani, Manager – Digital Innovation and Strategy, University of Sydney.

“For example, sharp objects, glass, and moveable chairs or tables are prohibited for safety reasons – there can’t be anything a person can pick up and throw.”

Phillip Rouse, Senior Manager, Organisation Development & Training at YJNSW added: “This will really make it possible for potential recruits to get a realistic feel for what a Youth Officer does on a day-to-day basis.”

There are no prerequisite qualifications for Youth Officer recruits – all the training is on the job. This can make it difficult for applicants to ascertain what the job is really like.

“This had led to us sometimes losing candidates as soon as they are introduced to the centre environment and start interacting with detainees,” Mr Rouse said.

“Through these projects we hope that will change.”

Managing Aggression, Virtually

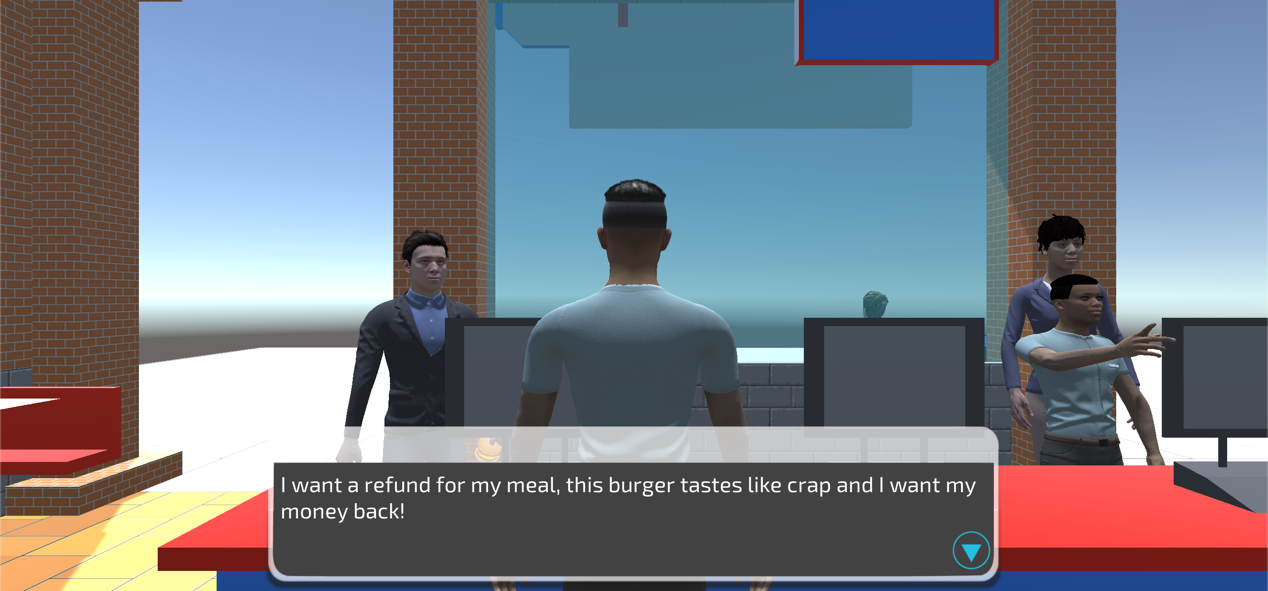

In the second project, the students created multiple training scenarios for Youth Justice staff to respond to aggression or violence by a young person in custody.

In the scenarios, participants can use a range of body language cues and verbal responses to try to keep the ‘youth’, an avatar, calm, or manage their escalating aggression.

“Heightened anxiety levels are often the norm for young people in custody – many come from traumatic backgrounds, and so they may be triggered by what is said or even how it is said,” Mr Rouse explained.

The students used voice recordings with different tones and temperaments to model varied young people in custody. The content, approved by Youth Justice NSW, was accessible (for example, it included subtitles). It was also underpinned by psychological research, from both the points of view of an officer attempting to de-escalate a situation, as well as the young person’s reactions to this.

Mr Rouse said the second project showcases the practicalities of working life for Youth Justice officers: “We show potential candidates that even though a Youth Officer only uses force as a last resource they should be ready (once trained) and willing to do so if required.

“Youth Officers also need to recognise the highly routinised nature of the work and the fact that they will probably encounter abuse and misbehaviour from our detainees. The simulation will therefore allow potential recruits ask themselves, ‘Am I suited to this work?’”

Mutual Benefit

The projects came together over Zoom, primarily last year during the pandemic. Despite the challenging circumstances, the students, all of whom are from China, found it incredibly enriching.

“Prior to this project, I had no work experience. Working on this project felt like working in a real company,” said student, Chenyue Hu.

Another student, Vera Wang, said the project gave her the confidence to interview for jobs in her home country, China, once she completes her degree.

“It gave me a better idea of how to interact with potential future colleagues – especially as we collaborated online which made it extra hard.” she said.

Ms Venkataramani said they students grew both personally and professionally from the projects.

“They went from being reticent to talk to the client to having smooth interactions,” she said.

On a professional level, the students learned to use Unity – a very current cross-platform game engine, which she said will make them “highly employable”.

Mr Rouse agreed, noting he was impressed by how the students navigated several steep learning curves – improving their English, mastering the use of new technologies, and working as a team for the first time.

“After we first met with the students, I was concerned that they hadn’t grasped the project outline. They were quite quiet,” he said. By the end of the project, however, his chief sense was gratitude: he even gave the students certificates of completion and reference letters.

The projects are currently being refined by the University’s TechLab team for compatibility with latest VR headsets, as well as scalability. They are due to be rolled out by Youth Justice NSW shortly.